I avoided reading Anatoli Boukreev’s two books for as long as I could for two reasons: First, I read Into Thin Air and wanted to be done with the 1996 tragedy and Chomolungma in general, and secondly, you can glean much about Boukreev from admirers and critics in their various articles and posts from time to time. (Goodness the conversation is still going!) Since I got rid of my prohibition on Everest books, I decided to finally read Boukreev’s own words, albeit translated.

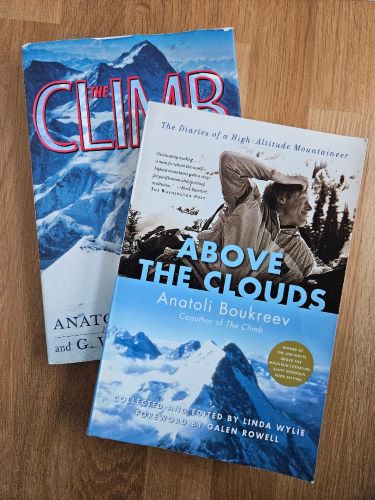

The chatter about Boukreev (which is pronounced as “boo-kre-ev,” saying both Es as separate syllables) was that he was either a villain or a hero, and the articles and posts would seem divided. I realized that the more you knew or read about Boukreev outside of Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air, the more sympathetic to Boukreev you would be. That’s why Boukreev worked with G. Weston DeWalt to write The Climb (1997), which told the story from Boukreev’s perspective. In a video interview, Reinhold Messner said that he thought Krakauer and Boukreev/DeWalt were both right and their stories were reconcilable.

(Ronald Turnbull wrote an interesting piece on the website UK Climbing about a 1996 Chomolungma disaster trilogy: Into Thin Air, The Climb, and Left for Dead by Beck Weathers (2000). Turnbull argues that the three books give the more accurate picture of the tragedy. In theory I suppose Weather’s book should be next, but I have no interest. Maybe that will change one day.)

Boukreev was a respected mountaineer long before the 1996 Everest guiding season. He was born in Russia and made Kazakhstan his home base to climb in the Greater Ranges. He was a climber first and foremost and sought ways to stay in the Himalaya. He was poor and often sold his climbing gear to pay for his way home or extended lodging until his next climbing opportunity. His gear was nearly always pre-owned and simply designed. The new commercial guiding ventures on Chomolungma provided him income, and a way to stay among the mountains longer.

I recently read Everest, Inc. (2024) by Will Cockrell and he shared new insight into the climbers that become guides on Chomolungma. The guides made more joy from getting their clients up to the summit and back than they were about their own summit successes. They generally enjoyed providing assistance and a degree of hand-holding, while watching the clients grow in their self-sufficiency. Cockrell also explained that guiding at altitude, above the so-called Death Zone, makes guiding on Chomolungma different than guiding lower peaks in the Himalayas or the Alps.

In The Climb, Boukreev and DeWalt confirm Krakauer’s observation that Boukreev would go far ahead of his clients and give minimal instructions, and appeared aloof. Krakauer wasn’t wrong, but Boukreev was a mountaineer trying to make mountaineers and he believed that the hand-holding approach did not prepare them for the challenges ahead.

The Climb was a book born in rebuttal to aspects of Into Thin Air and it needs to be read second. Arguably, Into Thin Air is a classic to many readers (I’m still mulling whether it is a classic) and I don’t think it’s a book worth reading without an interest in Krakauer’s book or the 1996 tragedy. I do think it deserves to be read after Into Thin Air.

Another book partly by Boukreev came out in 2001: Above the Clouds: The Diaries of a High-Altitude Mountaineer. Boukreev died attempting to climb Annapurna in winter during December 1997. His life partner, Linda Wylie arranged this book. The preface was quite long, and necessary to introduce the mountaineer and person. His reputation as a solid and competant mountaineer and mountain man is established more there than in the previous works in print. But the rest of the book, it’s just translations of Boukreev’s own writing. They’re authentic and relatable about connecting with the outdoors and mountains. It won the Jon Whyte Award for Mountain Literature at the Banff Mountain Book Festival, which is a gold standard.

I didn’t copy down any notes or quotes or page numbers in reading The Climb, but there were lots of copying and page numbers from Above the Clouds. It’s the latter where his most popular quote comes form:

Mountains are not stadiums where I satisfy my ambitions to achieve. They are cathedrals, grand and pure, the houses of my religion.

That was from pages 36-7. Although there were more, this one struck me as extremely relatable, especially as I grow more mature:

Standing there [atop Dhaulagiri in 1995,] I realized that I needed these trials and struggles, that they are important to me. It is with myself that I struggle in this life, not with the mountains.

That was from page 128, though not that it matters. And I might be featuring that quote because I have realized that most of life’s struggles, once we handle basic needs like food and shelter, is terribly internal with ourselves.

I also enjoyed his observations as a Russian visiting America in the 1990s, in Above the Clouds. They seem to resonate as relevant even today. Perhaps especially today. That’s not a statement about politics, but one about how great this county is, that anyone can be successful, but that the stakes of not being successful, because of it’s structure, made him appreciate the meager things of Russia. For me, in reflection, I get the structure and work hard to play well within the rules, but most of my reward isn’t from the tangible rewards, but from the time I spend outdoors and with friends. Those were things he kept returning to reflect on as well. It’s a beautiful book, and I see why it won at Banff.

I wish I had read Above the Clouds sooner. It stands alone. You do not need to read the conversations of Into Thin Air and The Climb. I think Krakauer’s observations about Boukreev were correct, but his characterization was limited to what he saw. So skip that, or forget about it altogether and go read Above the Clouds. You won’t regret it.

Well, thanks for dropping by. If you enjoyed this post, please sign up for my newsletter, which is the best way to get updates. And please tell a friend too; I am a humble hobbyist and don’t pay for advertising so organic search engine traffic and word-of-mouth referrals are all I’ve got. I just believe that climbing matters and you do too.