What I love about Mark Twight’s writing from the 1990s was that it was about alpinism. Boldly so. He had a purist view that had no room for rock climbing or bouldering; they were vehicles for skill building, but it was the big mountains in greater destinations that mattered, not our local crags.

I also liked that his writing challenged and even confronted my world view. His words got in my face like a Marine drill sergeant and demanded compliance and bravery. In his articles, everything was black or white, was trash or perfect. As a reader, you were either on the path to being elite, or you were missing the damn point.

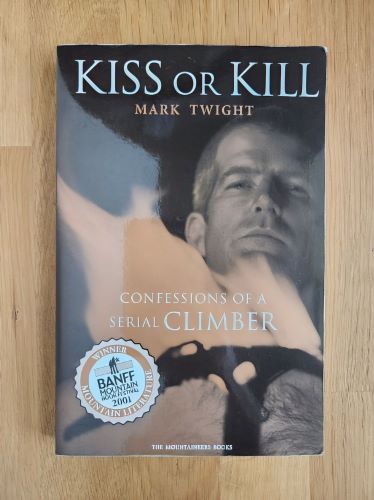

I can’t seem to recall when I first read Mark Twight’s collected works in Kiss or Kill: Confessions of a Serial Climber. It was first published by The Mountaineers Books in 2001 when I was 22, but the copy I own was the eighth printing, from 2010. I might have had another copy, but I don’t remember. I must have read his articles earlier because they left a deep impression on my young mind and confused me for several years: How could someone so bold and innovative in his climbing, that was so insightful and inspiring, and be such a dark person at same time? Was there something wrong with him, or was there some wrong with my perspective?

In case you don’t know Mark Twight, he was an American climber that was adopting the European fast and light style of alpine ascents, and applying them to bigger routes around the world, from Denali to Nanga Parbat. He climbed in the late 1980s until around 2000 with Jeff Lowe, John Bouchard, and later Steve House, and Scott Backes. He also founded Gym Jones. (If you don’t know about Gym Jones, here is what Alastair Humphreys wrote about it.) He doesn’t own it any more, but it went from being created by a guy with a pair of ice axes to be owned by a woman with a machine gun (in her profile photo).

I love how climbing can elevate us from a dull life of mediocrity. I needed that when I was growing up in the homogeneous suburbs, where everyone grew up to be a contractor, teacher, or insurance agent, and everyone watched football on Sundays. Part of it was the ethics of climbers; the Internet didn’t connect the climbing community, but climbers sought challenge, nature, and wanted to be above the baseline of what everyone else accepted as normal. Well, at least I did. Twight’s written words painted a picture of climbing that made mediocrity unacceptable, and wrote in confrontational and antagonistic tones using words like, “honor,” “justification,” “process,” “elitist”, “crazy,” and “against the consensus” like breadcrumbs on his path to a higher quality life, through climbing and alpinism.

I could make a essay just quoting Kiss of Kill throughout this blog post, but I might as well lend you my book. But there were two lines that I believed, but felt my understanding validated through his words. Twight wrote, “[As] technology and psychological advances increase, the danger and difficulty of the routes must be raised as well to maintain an equivalent human experience.” Humans, if we let ourselves, aspire to more, in general, and those that want to be pioneers, need new challenges, even contrived ones, and everything we do is somewhat contrived.

“People die. Alpine climbers die. It is part of the game.” Since the first time I read that, I have been wrestling with whether that’s something to acknowledge, accept, or prepare for? I’m not interested in dying and don’t want to hear news of a deathly fall. Yet, the stakes are high, for this contrived, beautifully enlightening thing alpinists do.

Both of these quotes, have a theme, I’d argue, of competition. Is climbing competitive? Twight was, and I don’t enter competitions, but I am too. We just compete in different ways. I generally compete for leadership roles, but I don’t enter climbing or golf competitions; I’d get crushed, if I care. I do care. I play different games. I think all climbers are competitive, but it’s about style, respect, and maybe a desire for a little fairly given and merited awe. Hopefully we get a little self satisfaction too, but I usually forget about that.

However, Twight was either more or less complicated than he portrayed in his black or white lens of his writings at that time. In an interview on the Enormocast (podcast episode 171), he told Chris Kalous that he wouldn’t have written what he wrote if he was who he is today, or how he sees himself now. Clearly, Twight was thrashing with his own self image and need for achievement in those days. He also confessed that he wouldn’t have quoted so many punk rock lyrics and titles if he had his own words to employ. Ever since I heard this, it’s made me think about the book’s value. In his book, Twight shares in a comment about a climb with him, Jeff Lowe said to him after reading the article, “It’s like we weren’t even on the same route.”

He was writing at the height of what Barry Blanchard classifies as “invincible days” of a young man’s life, when testosterone was raging and he thought people would die, but it wouldn’t be him. For Twight, I feel like, without a war fight in and to prove himself, like previous generations, he chose the hardest path of alpinism, which is already a hard path.

Kiss or Kill won the Jon Whyte Award — the award for mountain literature — at the Banff Mountain Film & Book Festival in 2001. Rightfully so. Kiss or Kill influenced my life, or at least the way I thought of it, and I certainly wasn’t the only reader to be jolted awake by Twight’s writing. My perspective on the spectrum of possibilities widened, both from the examples of what he climbed to how he talked himself into performing stronger. I didn’t need to follow his routes to change. And if you haven’t read it yet, I hope you resist feeling compelled to, too.

Well, thanks for dropping by. If you enjoyed this post, please sign up for my email updates through the T.S.M. Newsletter, which is the best way to stay current. And be sure to subscribe to a climbing magazine to support the climbing community and climbing writing in print.