Chris Kalman has made his life climbing. But there is no such thing as a perfect climbing life, “only a perfect life.”

Brewing hot coffee from melted snow in the dark is a chore, yet it’s part of a familiar early morning ritual. It’s an ideal period for taking in where you are: outside at play.

The climbing life is full of these moments and they are a little different for everyone. Still, I imagine Chris Kalman and his partners, Austin Siadak, Matthew Van Biene, Tad McCrea, on their upcoming attempt on Cerro Catedral in Patagonia doing something like this somewhere along the way. Together, they will be working to complete a new route on the 3,000-foot east face in Chilean Patagonia.

If you read Alpinist in the last year or seen the list of grant recipients for the Copp-Dash Inspire Award from the American Alpine Club, you might have already been introduced to Chris Kalman. He and I recently got to know each other over a long-spread-out email exchange during this Austral summer season in Patagonia. It turns out, despite having never met, our background had gone beyond both being from Northern Virginia, except he’s taken a very different fork in the road.

Kalman is fully embracing a climbing life and climbing full time. Our emails turned into a bit of an interview so we worked out this Q&A to share with you to share how the climbing life can become real.

TSM: Where are you climbing now and who are your partners?

Chris Kalman: Now I spend summers in Washington state, where I climb mostly at Index – an awesome crag of world-class granite – and winters in Cochamo, Chile, which features a variety of 1000 meter walls and cirques of beautiful granite. My favorite partners are still my first climbing partners I ever had, Grant Simmons and Miranda Oakley. We all went to college together at St. Mary’s College of Maryland, where we really started to learn to climb outdoors. That said, Grant lives in North Conway (New Hampshire) now, and Miranda in Yosemite – so I am branching out in the Washington state climbing scene more and more.

When did you start climbing? Was it hiking? An indoor gym?

I first climbed rocks at my dad’s cousin’s summer camp in the sierra nevada when I was 6 or 7 years old. I remember loving it instantly, but never thought about climbing again until my friend Colin Tharp, growing up in Northern Virginia, invited me to the Sportrock [climbing] gym [in Sterling, Virginia] with him when I was about 17 years old. At the time, I was kind of a punk skateboarder (which is definitely more dangerous than rock climbing!), and my aching limbs welcomed the change in disciplines.

When did you recognize that it was more than a recreational activity or hobby?

This is a really interesting question, with really no clear answer. Even though I am starting to carve out a career in the climbing industry now, it still feels recreational to me. I was brought up with a very strong ethic of community service and selflessness stressed from an early age. So for me, there have always been two kinds of activities: those you do for fun, and those you do for the betterment of people around you. I suppose the real answer to your question is that when I saw those two things could be one and the same, that’s when climbing went from hobby to … to something more. Now, I am very interested in climbing as a means: as a means to conservation, as a means to therapy (it has shown to be very helpful to post-war sufferers of PTSD), as a means to improving upon oneself. When climbing can move into these more selfless, service-oriented realms, then it becomes more than recreation.

Did you turn down a traditional career path outright?

I distinctly remember thinking when I decided to major in philosophy that at the very least, it should make it difficult for me to “sell out” and get a job working in an office. In reality, I think I knew more coming out of high school than I realized, and probably could have saved a lot of money by not going to college. For me, the “traditional” career path never felt correct.

Coming out of college, I started working for the national park service in Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado, and kind of instantly adopted the “climbing bum” lifestyle. I spent my first two paychecks on a plane ticket to Thailand for the end of the season, and have been working and traveling for climbing on and off ever since.

I would definitely stress to people that it is possible to work in a nontraditional career path while still working in a traditional discipline with a traditional degree. Biologists can find work in cliffside ecosystem analysis; engineers chemists and physicists are ideal candidates for jobs with gear companies (who are often sympathetic to climbing dreams and the need for time off); writers, photographers and videographers are the backbone of the climbing media, and can often find work for gear companies as well. It took me years to get up the courage to test the waters of the climbing industry, because I believed it was something just for the super-elite. In reality, the climbing industry is more of a “traditional career path” than you might think, and will often welcome good-hearted climbers with open arms.

Did a mentor guide you?

A lot of the joy of climbing for me has been figuring it out on my own. That said, I can clearly remember a few mentors. Scott Esser first showed me how to equalize a 3-point anchor at the Suzuki boulders in RMNP (I haven’t seen or talked to him in years, but I still remember that). Jess Asmussen – one of RMNP’s lead climbing rangers – took me on my first multi-pitch, was there for my first trad leads, and has

been a long-time hero of mine not just as a climber but as a role-model. He’s just a great human. Jeremy Long – one of the trail crew leaders of old at RMNP – took me on my first alpine route, Pervertical Sanctuary on the diamond. There were times in my naivete, especially when hail was falling on us and lightning was striking with frightening proximity, that I thought we’d probably die up there. He smoked cigarettes and smiled through the whole experience, and patiently explained crack climbing and french-freeing to me at 13,000 feet as I grovelled my way up the crux pitch first crack before we bailed.

Who’s your hero in the climbing world? Messner? Tackle? Honnold? Kennedy?

Those guys are all amazing. John Muir has to be high on my list. Peter Croft is an incomparable badass. But really, I have to say my climbing heros are my friends Grant Simmons and Miranda Oakley. Those two embody all the best things about climbing: joy, skill in movement, sharing their love with others, and selflessness; and none of the worst: ego humping, derision of other climbers, anger at the crag or gym when you fall off your project, posing. I’d rather be a good human than a good climber any day. My hope is that climbing can help in that regard. After all, every time you fall, you remember how much you have to learn, right?

I don’t know if you heard about the death of Mark Hesse. He lead an active life climbing and supporting the community. What does it mean to have a full climbing life?

I did hear about this. I don’t know if this was a bad year for climbing, or if I have just taken more notice of climbing deaths, but it seems the grim reaper has been lurking around every corner lately. To me, there is no full climbing life, there is only a full life. And a full life is not a destination, or an end-goal, but a process and a pursuit. For those who choose to make climbing part of their pursuit of fullness, I would urge them to recall that the real work is not in sending five-point-whatever, but in bringing light to yourself and those around you by constantly trying, constantly falling, constantly smiling, and laughing, and trying again.

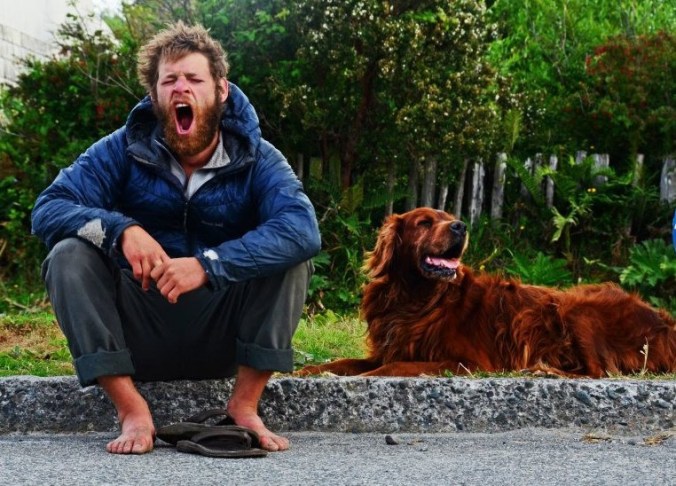

Chris Kalman climbs in Cochamo, Chile in winter and spends his summers in Seattle where he is starting up a Pacific Northwest branch of the guiding company Treks and Tracks. As a 24-seven climber, he is also supported by Cilo Gear, Madrock Climbing and NW Alpine.

Thanks again for stopping by. If you enjoyed this post, please consider following The Suburban Mountaineer on Twitter and Facebook.