After 15 years, this is my last entry here on The Suburban Mountaineer, and it’s official channels like the newer T.S.M. Newsletter.

In 2010, I did not intend to start reviewing so many mountain books and making book reviews the most common entry here. That just came naturally. At first people started sending me their books. Some of those submissions were bad, too. Somewhere then I realized I just wanted to do a reader response. I think the most fun was reflecting on passages in articles from Alpinist Magazine.

This blog has opened lot of opportunities. Its best output has been making friendships and acquaintances with Katie Ives, Bob Schelfhout-Aubertijn, Elizabeth McDonald, Dawn Hollis, Joanna Croston, David Smart, David Stevenson, among others. Well, we’ve talked more than shop, I have their email, and conversed multiple times initiated by me at times and sometimes they reached out. That has meant a lot to me. I am still in awe that I–an out-of-shape climber–have contributed to Alpinist Magazine multiple times and was included on the damn dust jacket of Hollis’ Mountains Before Mountaineering (2024). I am going to bore my grandchildren telling them about these accomplishments. They’ll say “so what, granddad,” or whatever kids will say in the future, but I won’t care.

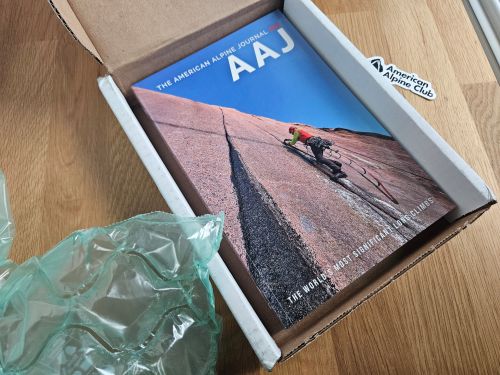

Coincidentally, yesterday afternoon, I received the Black Diamond catalog for Winter 2025, which I only mention because it’s fun, but I also received the 2025 American Alpine Journal. In this AAJ, I finally have an entry. No, not a route, gosh darn it. (Wouldn’t that have been something?) I have contributed a book review, of course. You can find it starting on page 369.

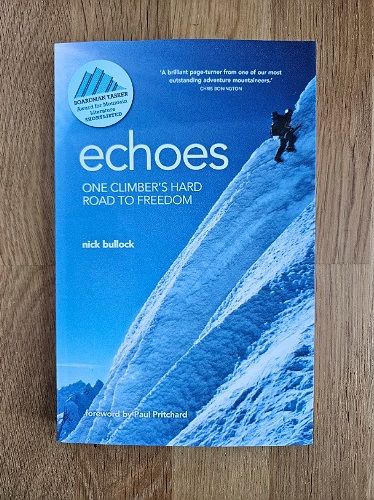

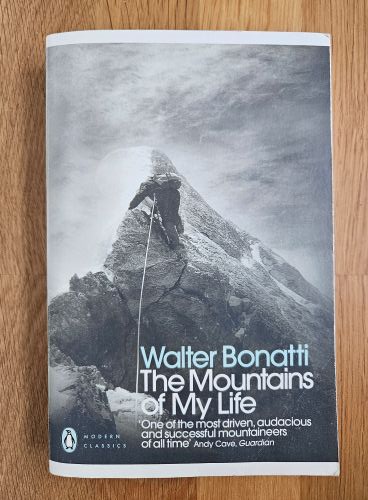

So where does the list of climbing and mountaineering book classics that I have been developing and talking about all these years currently stand? Well, it’s practically done. I have the list. I know what the classics are. But I am not sharing it now. I’m personally satisfied with it (as of autumn 2025, I mean, things change, right?) If you recall, the impetus for that quest was that I wanted to know what were the limited titles that belonged on my small, limited bookshelf when Natalie and I owned a small condo in Alexandria, Virginia. I have the list, but not the time to write about it and give it the justice it deserves to be publicized. Walter Bonatti’s book is not on there, so please stop calling it a damn classic. It’s not. Into Thin Air, is that on there, you ask? Well… Maybe I will share one day. But not right now.

So what am I doing next? My kids have gotten older and they need me more and in different ways than when they would play on our wall-to-wall carpet of the living room, just glad I was in the room with them, and let me sit on the couch sipping coffee from my green mug and read Alpinist. Also, the nonprofit I run has grown and needs me at a greater capacity. Unfortunately, I rarely have a peaceful interlude between appointments where I can draft a blog post at a cafe, like I often did in the early years of writing here. Gosh, I really miss those days. (I loved the stops at Caribou Coffee in Washington, DC the most, when there was Caribou Coffee locations in DC.)

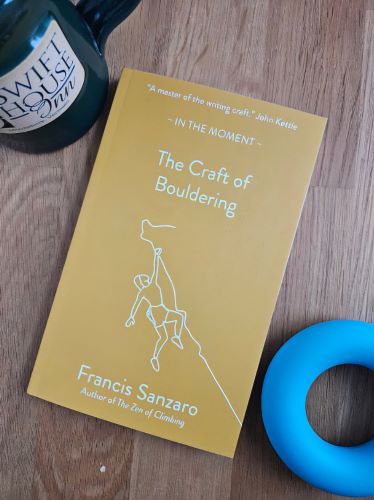

And staying fit is taking up more and more time. It’s harder to be even moderately thin and strong over 45. I might make it to my climbing gym more frequently, actually. That would be delightful, wouldn’t it? I’ll be happy to belay twice for you for one for me, too. I have a brand new BD harness and my friend Nathan still hasn’t asked me to give him back his Gri Gri, so I have that handy. Hit me up if you’re in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

I hope to still contribute to Alpinist, the AAJ, and other publications from time to time, when I am invited or inspired. The Suburban Mountaineer on Facebook and my profile on BlueSky will still bring up mountain climbing book content from now and then; I’ll never get away from it. It’s wonderful and really consuming, isn’t it?

Thanks for reading. Sincerely: Thanks for reading my humble hobby blog. You really enhanced my life.

One last thing… Please don’t forget to subscribe to a climbing magazine and if you already do, please renew your subscription. It supports the climbing community and climbing writing in print. And print has way more magical powers than any social media post or stream, am I right? Go subscribe and be well.