Like a lot of things from Outside, the headline is a little misleading and the article has a little unnecessary edge. And the following social media captions have claimed implied that gym access is the AAC’s top priority, and that elitist climbing gyms are turning climbing into golf clubs. Well, let’s sort this out. The AAC’s idea is a good idea. It’s a best practice I hope most if not all gyms adopt. But the headlines and arguments cast by MacIlwaine are a little out of proportion.

Climbing dot com of Outside Magazine published an article by Samantha MacIlwaine, Can Climbing Outrun Its Own Elitism with Inclusive Gym Pricing? The sub header reads: “Indoor climbing has gotten so expensive that the American Alpine Club officially considers it an ‘access issue.’ Is there anything we can do to stop climbing from becoming an elites-only pursuit like skiing or golf?”

MacIlwaine is responding to the AAC creation of a Pay What You Can Toolkit for climbing gyms to start their own “PWYC” program. It was shared in with AAC members in their “The Clubhouse” e-newsletter on or around July 23rd. I didn’t even read that newsletter until reading MacIlwaine’s article. If I had, I would have thought it was a nice idea, appreciated the AAC’s leadership, and moved on. But goodness has this generated a lot of discussion, and not all of it was accurate.

Our age of social media has also caused others to read the headlines in their feed and make it to be the biggest issue in climbing. Are you kidding me? Climate change and access to genuine public lands are still at the top, and should remain so. I initially re-tweeted a post on Twitter/X in solidarity for the angle of justice; I couldn’t afford the monthly dues, let alone the registration fee, when I lived in Alexandria, VA, and climbed occasionally via day passes. Here in Lancaster, PA I could afford to join my local gym for half the price and I showed up two-to-three times a week making it a bargain and I was stronger than ever. Then I thought about the differences in quality and experience, and deleted my re-post.

I think the data MacIlwaine shares about how little Americans spend on gym memberships and fitness is probably right. But I don’t think that it’s the right comparison. Climbing gyms are not fitness equipment gyms. They’re, and forgive me for this, more akin to tennis clubs. Tennis clubs are also sport-specific athletic and social clubs. They both have practices, matches, organized competitions, coaching, and sport-specific equipment. Some tennis clubs have PWYC programs, and many more do that don’t advertise them. Why? Having a dedicated players that grow are good for clubs, but they don’t talk about them because its political with its dues paying members. I have never heard of this at a ski resort or a golf club.

Then there are what parents spend on their kids sports. Have you looked into travel baseball or soccer teams? The costs of fees, uniforms, transportation, lodging, and coaching, all amount to big business for that investment companies are buying. It’s not a gym cost cited in the AAC toolkit or MacIlwaine’s article, but I think that it deserves some attention. My point is, there are households that value something more and are willing to spend more. Are there lower cost activities to get the same result; it comes down to getting scouted and supported by generosity, hence a PWYC model of a different sort.

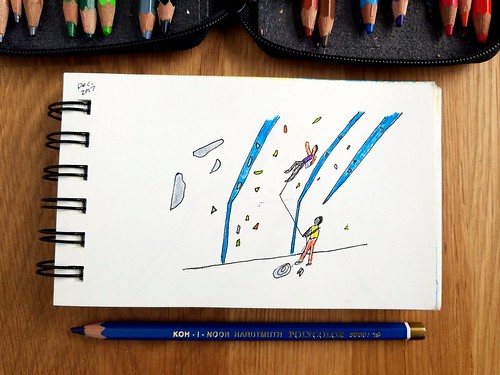

The nuance here is that the AAC understands that gyms are how many climbers come to climbing in the first place. Gym-to-crag programs are essential today, and outdoor climbing stewards know that it’s key for safety and conservation. And the gym has effectively pushed the boundaries of climbing beyond the outfitter in mountain towns outward into nearly every community, regardless of the presence of mountains and crags. In my opinion, climbing at the gym is its own category of climbing and still, ultimately a simulation, but it has made some amazing performance gains for climbing the real thing.

I think the good people at the AAC could see the climbing gym world serving an increasingly affluent group, as is stereotypical image of skiing and golfing or even competitive tennis or swimming. I will say from experience, that the resistance to keeping prices elevated at indoor facilities will find support and an affordable option if there is advocacy and demand from a market. For an example from golf, Schnickelfritz competes in golf competitions but is one of the few that doesn’t belong to a golf or country club (which are different, by the way.) In fact, we have found ways to practice and save costs, and using similar PWYC or youth discount programs, like Youth of Course. It makes his rounds just $5.00.

The AAC has taken a policy and advocacy approach to support its members and it still comes higher than gym access. The institution focuses its advocacy on protecting public lands, ensuring lands are open to human-powered recreation, safeguarding fragile mountain and climbing environments, and combating climate change.

Of course, climbing is fundamentally and ultimately an outdoor activity. Climbing gyms may be the new gateway for new participants, but climbing will always be available to the climber. Pulling plastic, which I enjoy too, is a different activity and beneficial to outdoor climbing, but it’s not rock climbing. If gym access were to become inaccessible to a lower-income population, climbing gyms will change, but maybe the better climbers will be the adventurous ones outside at the crags and the mesmerizing big walls.

The AAC’s PWYC recommended best practice and toolkit is smart for inclusion, equity, and our climbing community. I support it. And it’s not the top new issue we need to spend all of our time focused on. Go climb, indoors or outside. And tell your gym about the toolkit, if they don’t have a PWYC program already.

Well, thanks for dropping by. If you enjoyed this post, please sign up for my newsletter, which is the best way to get updates. And please tell a friend too; I am a humble hobbyist and don’t pay for advertising so organic search engine traffic and word-of-mouth referrals are all I’ve got. I just believe that climbing matters and you do too.