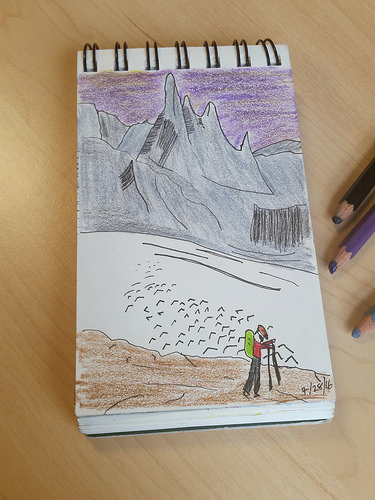

A couple of years ago Jason Stuckey shared with me his high-resolution photos from his first ascent with Clint Helander of Apocalypse Peak in Alaska’s Revelation Mountains. I recently stumbled upon them cleaning up some files. They’re dazzling. Dizzying.

I zoomed in on Clint. At first he appears as a mere stick figure on a steep snow field, but closer in I could see the contours of his helmet, and count the number of pickets and screws hanging on his harness. Then, I saw something I hadn’t noticed before: Clint was looking in the same direction Jason was, and I was, in taking in The Angel, another 9,000-foot tall mountain (9,260 to be precise) over the valley. He had made the second ascent a year earlier.

Looking at these photos from my laptop in my Washington, DC-area condo at 6:30 a.m., I feel a sharp, cold gust brushing my exposed skin, and a little where it isn’t. The clean, unfiltered sunlight is blindingly bright even though my lenses are dark, almost black. It’s a bluebird day, rays bouncing sharply off the snow. And I can imagine my calves stretching, getting oddly warm in an unwelcome way, as I’m standing on my front points.

Then I remember that I have to wake the kids in an hour, and I am supposed to cover a Congressional hearing on the Hill at 10:00. I must remember to wear a tie today. I need to be there to know what the tone of the meeting was and whether any promises were made so I can hold them accountable. If I don’t, no one else will. At least that’s what I strongly believe, even if it might not be entirely true, or necessary.

Damn it. I want to be here. Living with my family. Fighting for my cause. But I want to be in that photo too.

The Passionate Divide

Adam Campbell, an Arc’teryx ultra-marathoner, lawyer and reader, wrote an essay in the fall-winter issue of the brand’s Lithographica publication titled, “The Passionate Divide”. Campbell loved three things: running, legal challenges, and reading. They are his passions and while he considers himself fortunate, as many people don’t have even one passion, he is simultaneously cursed by having more than one. His ambition made him want to do well at both. Except improving at one meant sacrificing time that could be used to improve on the other.

Campbell talks about the quest so many people talk about everywhere: elusive work-life balance. Natalie has learned, and sometimes reminds me that balance doesn’t mean 50-50; balance can be 70-30 if it makes sense and you accept it. She’s right. But I haven’t figured out what the right arrangement is either.

The conflicts Campbell faced broke up his marriage and ended his time at the law firm where he worked at the time. And he stopped racing. He worked to find his motivation again. Then he realized that the idea of balance is all wrong — which is more to Natalie’s point to me. Campbell wrote, “balance means that two things are in opposition with one another; they are counterweights with nothing in common.” But we both know that isn’t true. Campbell’s passions are part of his whole. My passions are part of me combined. As Campbell also wrote, “Integration was the path to less internal conflict… Be gone guilt.”

One Unresolved Matter

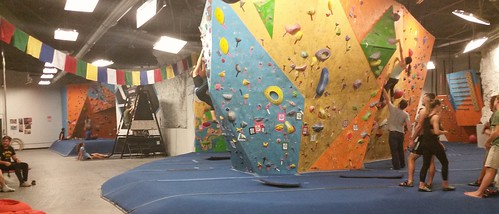

Is climbing still mainly an outdoor activity in the mountains? That’s the way I prefer it. But climbing is in just about every peakless metro area through gyms. Even when I go climbing these days, it’s mostly indoors. All that’s great except when it’s the outdoors that we crave. And this presents the issue that Campbell’s approach can’t resolve.

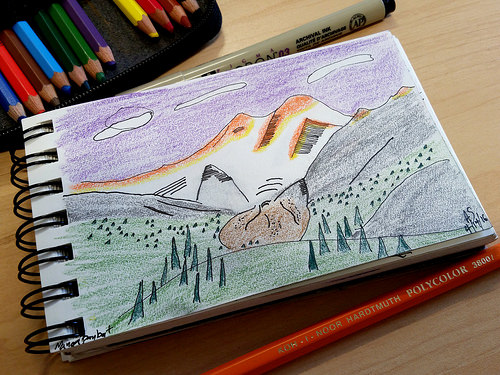

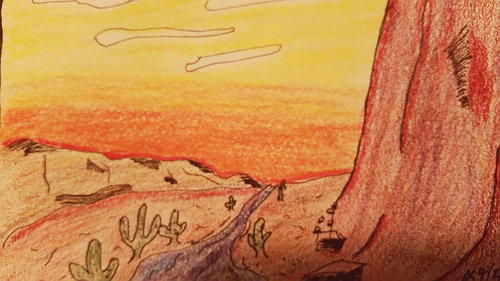

Campbell’s approach has shed a lot of light on my passions for being a stronger climber, better at my job, a better husband, a better father, a better fantasy baseball manager, and a better artist. I realized that I compartmentalize things too much. Which means I often played king of the mountain with my passions. Now I realize that it’s okay so long as I recognize that they are not competing against one another.

After contemplating this for a long time, I’ve realized that our self identity isn’t just made up of one thing, even if it’s one thing at a time. One word can’t describe most of us, whether it’s climber, friend, or guitarist. We’re the combination of many things. And though we may not be great at any of our roles, the sum total can be beautiful. In fact, for us flawed mortals, perhaps only through the whole can we be beautiful.

However, resolving the turmoil of the passions that I can enjoy in and around this city where I live is one thing. I even have to work at trying to be comfortable and embrace the urban lifestyle. (I think I am doing better than I was a few years ago.) It is the passion for a job in the city versus a more wild surrounding that I am still having trouble resolving. Resolving it for passions — which are, broadly speaking, hobbies — is a different matter than the environment.

Passion for Place

Looking again at Jason’s photographs, I sit quietly and feel the wind and absorb some of the sun’s rays. I imagine loosening the pic of an ice ax, being careful not to break it, and reaching higher to chip into a firm bite of ice.

But I’m not in Alaska. So maybe after the hearing, I’ll leave work early, get Natalie and the kids and go play by the river. That actually sounds pretty darn good too.

Thanks again for stopping by. If you enjoyed this post, please consider following The Suburban Mountaineer on Twitter and Facebook.