So we’ve been discussing how to determine who are the best climbers of all time. We’ve gotten good guidance from Katie Ives of Alpinist and mountaineering historian Bob Schelfhout Aubertijn. I encouraged you make your own list of you thought was deserving — some of you shared your picks on The Suburban Mountaineer’s facebook page — thanks; they were helpful in ensuring the final list considered a complete list of nominees.

At the end of this post, I share the list I wrote over two-months ago before I started this quest. Now, after reading this criteria for determining the best, my original set of names seems laughable in some respects. I saved chuckles for you on that note for last. First, let’s look at the rubric:

BARE MINIMUM FOR CONSIDERATION

1. Objectives — The peaks and routes sought must be of a grand scale and pushed the limits of what was believed to be possible at the time.

2. Climbs’ Duration —– The American Alpine Journal requires that the entries be about climbs longer than a day and that rule ought to apply here too. It will be the minimum threshold on this point. Climbers will get additional favor if in addition to scaling the peaks in their back yard, also ventured into foreign territory where customs and complicated logistics are part of the broader route to the top.

3. Routes’ Difficulty — The difficulty must include the challenges of an alpine climb and at the highest grades of the period the climber climbed. Some handicapping (sorry to use a golf term, folks, but it works well here) is done here; for example, using oxygen tanks at altitude in the 1930s is quite different than using them in the 1990s.

4. Lead Historic First Ascents or Established Significant New Routes — This means even memorable repeats are out and so are strong climbers that collect climbs or did things for their nation. So sorry to Ed Viesturs (a hero regardless) and Erhard Loretan (a strong high altitude climber), your quests were thrilling to follow, but you don’t pass the bar.

SEPARATING THE GREATESTS FROM THE GREATS AND HONORABLE MENTIONS

5. Creativity — This may have been the key factor, though clearly not the only one. The standard here is about conventions. Did the climber work within the conventions of the day to excel? Or did the climber innovate to disregard the normal path. Examples can range from the invention of specialized gear to the establishment of a new route over previously thought unclimbable terrain.

6. Climbing Style — This could be the most subjective factor. It might also be the one factor where the values of “great” climbers 100 years ago are quite different from what is valued today. For this test, the climbers must embrace and exhibit the use of small teams and taking little gear. This does not require the climbers to have adopted a fast and light ethic, but rather an independent alpine approach with only a few companions, little support and minimal fixed ropes.

7. Purity of Approach — While approach is related to the climber’s style, it is also about what the climber seeks and his/her respect for the mountain and any traditions related to the culture around the peak. A climber seeking a mystical or spiritual experience will be rated higher than someone looking to be in the record books.

8. Influence on Climbing — It’s theoretically possible that a climber that fulfills all of these criteria might not be influential. To be influential, the climber must have notoriety. Climbing in a vacuum by not sharing your first ascents, style and other accomplishments is wonderful and pure but doesn’t give to the climbing community. If anything, climbing in secret gives doubt about first ascents and attempts for future climbers. Notoriety is an element of being among the greatest because they’re example leads a way for others to follow. Notoriety isn’t necessarily synonymous with influence and I recognize that as well, but it is an important factor in determining who among us is the greatest.

I’d appreciate any thoughts or reactions on this list of factors for consideration. Shoot me an email, leave a comment or hit me up on Facebook or Twitter.

Okay, so here it is. This is my original list as promised. Before you laugh too hard, remember that it was before I got your input and developed a rubric. This list was merely a starting point. If you chuckle, please don’t keep it to yourself. Let us know what you thought.

The list is also 17 names and not 20 as originally advertised; after I jotted down the unranked list I went back only to share it for a couple of special purposes. It remains unranked now as I first wrote it because to order them now would be based on what I know and believe now, not what I thought then.

Reinhold Messner

Jerzy Kukuczka

Denis Urubko

Fritz Wiessner

Fred Beckey

Voytek Kurtyka

Barry Blanchard

Mark Twight

Steve House

Vince Anderson

Marko Prezelj

Lionel Terray

Anatoli Boukreev

POSSIBLE HONORABLE MENTIONS:

Colin Haley

Hayden Kennedy (up and coming)

Ueli Steck

Simone Moro

Here are some quick notes reflecting on my early scribblings:

Some of the names, like Twight, House and Haley are rather contemporary. I wasn’t sure they could stand a test against some of the old school mountaineers, and yet I suspected that they’re modern attitude toward the sport might match up to some historical accomplishments.

I left off Ed Viesturs. He was once a hero to me and he is still a role model. While he means something to many Americans, his mountaineering accomplishments were not progressive or influential. He was conservative and enjoyed his quest to reach the top of all the 8,000-meter peaks. I like him for that but he can’t be among the greatest in the scope of the history of climbing.

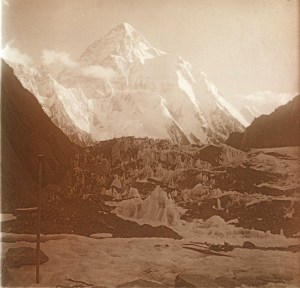

Voytek Kurtyka has recently become my favorite alpinist. He climbed on his terms, skirted death many times from a Zen-like outlook, and made some significant first ascents in the Karakorum. Yet, even when I wrote this, I wasn’t sure he’d make it to the final list. I’ll let you know…

I appreciate you stopping by for a read once more. If you enjoyed this post, please consider following The Suburban Mountaineer on Twitter and Facebook.

Climbing matters, even though we work nine to five.

Click here to read the next post in this series.