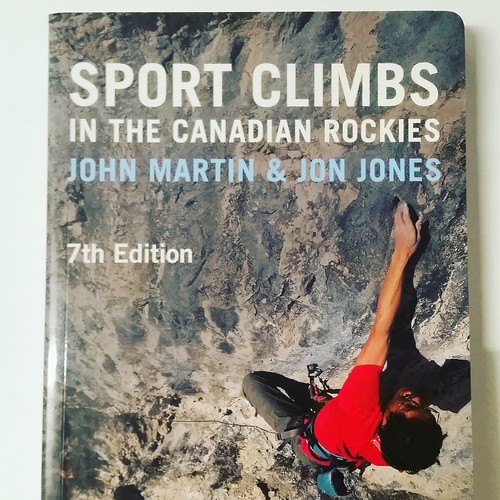

Martin and Jones book is new again, this time in color.

So I hear that you’re moving to Canada. That’s great! (And I understand that you are dismayed at prospects of the impending Trump administration.) So I jotted down some quick recommendations for you on your move.

If you move to PEI, be sure to live near Charlottetown and go have a Gahan beer, but be careful with those sandy cliffs. If your French is up to snuff, you won’t feel like an outsider in Quebec, and there is excellent water ice north of Montreal. If you’re heading to Toronto, there is some modest climbing in Ontario — oh, and you’ll have to get used to buying milk in a bag. British Columbia is diverse and insanely beautiful.

But Alberta… ah… Alberta. That’s where you should go. Settle into Calgary or even Edmonton for a “real job” with lots of benefits and paid vacation time, embrace a hockey team, and drive to the Rockies (the real ones) in a couple of hours. There is ice climbing and several amazingly well developed sport and trad climbing areas throughout the Bow Valley.

Never heard of the Bow Valley you say? Well, have you heard of Lake Louise, Canmore, or Banff? That’s the neighborhood.

So once you have your visa or immigration papers, you’ll need just two books: 11,000ers of the Canadian Rockies by Bill Corbett, which I recently reviewed, and Sport Climbs in the Canadian Rockies by John Martin and Jon Jones. Both have been updated with new editions in full color this year.

When the Weather is Warm

Now, let me tell you about Sport Climbs in the Canadian Rockies...

There are other guidebooks for the area, but this one has been updated most frequently and most recently. In October 2016 the 7th Edition was published. It also covers the biggest territory; not only Banff National Park of Bow Valley, but that and more in the neighboring and contiguous valleys. In total, it covers over 2,300 routes including climbs in Banff, Canmore, Lake Louise, Kananaskis Country, and the Ghost River region.

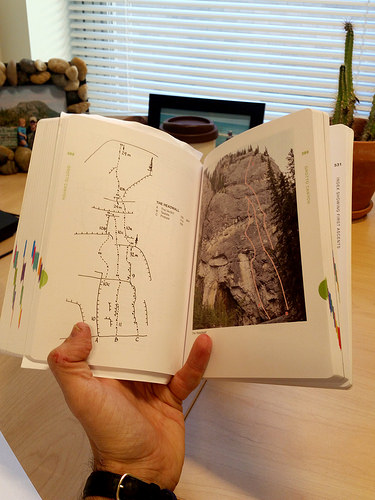

It’s a genuine techincal guide to the region and the routes. Most of the content are illustrated through topos, rather than photos. There is a reason for this and some practical benefits: First, the valleys are narrow and portions are blocked by other nearby features. Properly descriptive photos are broadly impossible, however, there are photos wherever they were practical.

Secondly, with the majority of the images in topos, the guide lets you see in clear terms what might not appear in a photo, such as belay stations, or a chimney that might only be viewed as a shadow. The minimal descriptions in prose make these maps something to get lost in just in planning.

Martin and Jones have updated the guidebook with this 7th Edition to account for the radical changes brought on by the 2013 rain-on-snow floods. Some routes start lower, due to excessive erosion, while others are starting much higher because of deposited rock and soil. This has complicated some approaches and the start of some climbs. The authors recommend a long stick clipper in these areas, which the guidebook points out.

It’s a beautiful guidebook whether you’re moving to Canada permanently just visiting, or live in the area. Regardless who you wanted to win America’s 2016 presidential election, you can forget all about it here in the corners of the Bow Valley.

Appreciative Note

I also want to thank my good friends in Alberta, Joanna and Jason, who separately extended an invitation to Natalie, the kids and I if we had to flee the states after the election. (And they offered way back in the summer before election day; that makes some good friends!) We appreciated the offer, but Natalie and I decided to stay; the American crags, parkland, and climate needs more voices to weigh in loudly here.

Thanks again for stopping by. If you enjoyed this post, please consider following The Suburban Mountaineer on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

The question of who actually stripped the camps stocked with sleeping bags and food late in the expedition in 1939 is addressed anew with evidence. Likewise, the most controversial expedition to the Karakorum, the 1954 Italian assault on K2 is revisited — with evidence. Conefrey reevaluates whether Walter Bonatti was a blameless victim and if those that made the first ascent, Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni, did or did not actually run out of oxygen as they claimed, or if they did, what does that mean for Bonatti and his allegations of Lacedelli and Compagnoni? In both instances, the evidence could be interpreted a little differently, and perhaps discounted altogether, but it doesn’t necessarily diminish the reevaluation of events. And if anything, may make the history come alive again for a younger generation.

The question of who actually stripped the camps stocked with sleeping bags and food late in the expedition in 1939 is addressed anew with evidence. Likewise, the most controversial expedition to the Karakorum, the 1954 Italian assault on K2 is revisited — with evidence. Conefrey reevaluates whether Walter Bonatti was a blameless victim and if those that made the first ascent, Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni, did or did not actually run out of oxygen as they claimed, or if they did, what does that mean for Bonatti and his allegations of Lacedelli and Compagnoni? In both instances, the evidence could be interpreted a little differently, and perhaps discounted altogether, but it doesn’t necessarily diminish the reevaluation of events. And if anything, may make the history come alive again for a younger generation.