City living. (All rights reserved)

I once tried to leave Washington, DC, uproot my family, change jobs, and settle permanently among the Green Mountains of Vermont. Ultimately, I called off the effort and decided to stay (at least for the time being,) and I can happily report that I am at peace about it. I talked about this experience in June as part of my post How Your Mountain Dreams Might Be a Trap, and it spurred a lot of comments and a few direct messages.

The biggest question was how did I make peace? Well, after a lot of introspection, I identified some things that work for me almost like therapy. Coincidentally, it came to 10 things. The list could have been eight or nine, but without trying it’s 10. However, there are two things about my situation that might give them a little more context…

City’s Wilderness

When I was younger, my Uncle Tom brought me on adventures hiking and climbing in the Adirondacks. Those trips make up many of my formative experiences. When he passed away from cancer, too young, shortly after I moved to Washington, I lost the only person I knew who understood wilderness from experience. I moved to Washington for my career, and for the first 10 years, while I was fulfilled in my job (and still am,) I felt lonely except for my wife and work colleagues. Nobody I knew shared my interest in the outdoors like I did with my uncle.

During that time, I was frustrated by what most people I met thought of when they thought of outdoor recreation. In fact, saying you love the outdoors or mountains means a lot of different things to different people:

- Camping. When I say I love camping someone might want a road-side camp involving a stereo, cooler, charcoal grill, and a big motorboat. I want the backcountry with quiet, a small stove, and having walked in.

- Trails. When I say I love trails someone might want to be on an ATV or dirt bike. I love trails for walking in the backcountry free from motor vehicles, and sometimes free from mountain bikes and horses too.

- 4WD. When I say I love my four-wheel-drive vehicle someone might mean that they love off-roading, mudding, and driving for thrills across big, open landscapes. I mean that I love my Subaru and that it gets me through the snow to ski country and down dirt roads to the trailhead, and once it gets me to the big open area, I prefer human-powered activities like hiking, climbing, kayaking, cycling, and so forth.

So just like in Upstate New York, there were a lot of people around me that didn’t share my values or experiences. Without making city living an “us against them” game, which I was doing, I had to be blunt with myself about what I valued. I think, fundamentally, this is why I have always identified more with climbers than someone who calls himself or herself a hiker. When I did find people of similar interests and values for the outdoors, they were typically climbers with a naturalist bent. And most climbers on social media and the events that I have made friends with typically are.

Since I realized this, I worry about millennials that came to climbing through a gym and have none or little background in respect for climbing outside, but that’s a conversation for another time.

Access issues outside Nat Geo HQ.

Who are You Without Climbing?

In Alpinist 54, Hayden Kennedy shared in his article”Light Before Wisdom,” how climbing and climbing-success consumed him, and after an injury, he was forced to face a question similar to mine: “Who am I without climbing?” He came to realize that there was more to alpinism than climbing.

Adam Campbell, an Arc’teryx ultra-marathoner, lawyer and reader, helped illuminate this idea a little more. He wrote an essay in the 2015-16 fall-winter issue of Arc’teryx’s Lithographica publication titled, “The Passionate Divide”. I shared the importance of this to me back in April:

Campbell loved three things: running, legal challenges, and reading. They are his passions and while he considers himself fortunate, as many people don’t have even one passion, he is simultaneously cursed by having more than one. His ambition made him want to do well at both. Except improving at one meant sacrificing time that could be used to improve on the other.

Campbell talks about the quest so many people talk about everywhere: elusive work-life balance. Natalie has learned, and sometimes reminds me that balance doesn’t mean 50-50; balance can be 70-30 if it makes sense and you accept it. She’s right. But I haven’t figured out what the right arrangement is either.

The conflicts Campbell faced broke up his marriage and ended his time at the law firm where he worked at the time. And he stopped racing. He worked to find his motivation again. Then he realized that the idea of balance is all wrong — which is more to Natalie’s point to me. Campbell wrote, “balance means that two things are in opposition with one another; they are counterweights with nothing in common.” But we both know that isn’t true. Campbell’s passions are part of his whole. My passions are part of me combined. As Campbell also wrote, “Integration was the path to less internal conflict… Be gone guilt.”

For me, separating my career in Washington from my love for the outdoors and mountains, I realized was a problem. I could be in one place and love the other. Because I did and that was the truth about me. If that doesn’t quite make sense, I had to mull over this notion for months until I even started to put it into practice. But the guilt (or frustration with myself) is nearly gone now.

10 Ways to Cope in the Big City

For those of us in a densely populated urban area, some interests and hobbies are more easily fostered than others. Baseball, like all pro sports, for instance is easier to come by. It’s broadcast half the year, ballparks are almost everywhere and people of all ages can participate, even if it’s just softball. While on the other hand, a passion for mountain life must be conjured-up and summoned in different ways.

These are the things that I have learned to practice that help me cope with my unsettled need for the mountains and outdoors.

- Gyms. Embrace indoor rock climbing. I’ve always climbed indoors, but I never really embraced it as legitimate climbing and a place to enjoy. The gyms are almost everywhere these days. There you can go and keep practicing your footwork and knots with purpose. Once I got over being the old guy at the gym that boulders alone, I started visiting regularly and loving it. As a general principle, the act of climbing (hiking or whatever) is more important than reading and discussing it.

- Visit. Visit isn’t actually the right word; rather make pilgrimages to the mountains and treat them as such. Keep the time special and disengage. Really disengage. Even if it’s only once a year.

- Sanctity. Have some sacred things. For me it’s a fleece pullover, my boots, and my tin camp mug. They only come out when we go outdoors, even if it’s just Cactoctin Mountain.

- Reminders. Buy souvenirs when you’re at the places you love. They’re only tacky in the shop. When you get home, people see that hat or mug from your destination and strike up a conversation and boom: You’re talking about your trip.

- Subscribe. Subscribe to your favorite climbing magazine. For me, it’s Alpinist. Having something fresh arrive in my mailbox periodically about climbing awakens my senses, at least in my daydreams after reading.

- Clubs. Join the American Alpine Club, Access Fund, and whatever local conservation group is in your area. Then show up to the local meetings or special events when they come through.

- Advocate. I do advocacy and government affairs for a living, but my favorite work is when I am volunteering to support the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, Alaska Wilderness League, or responding to whatever call-to-action the Access Fund or Patagonia sounds. Speak up for what you care about, even if you’re just signing a petition or persuading a friend (without fighting) to change their position.

- Gear. I don’t mean getting new gear. New gear without being put to action empties the wallet and doesn’t fill the void in your heart. I used to buy gear and gizmos (I have a backpack fetish, it seems) to fill the void of actually going outside and playing. So resisting buying things I don’t need was important to put money into the gym and the pilgrimages. In the end, I got way better value.

- Read. I have always been reading climbing books, from classics by Dave Roberts, to long forgotten like books by John Long. Reading books nominated for the Boardman Tasker Price for Mountain Literature or Banff Mountain Book Competition never disappoint either. You have to be careful when you get jealous over the subject’s dedication to the climbing or vegabond life sometimes. If that happens, take a break and look at yourself as a whole again.

- Wheels. If you can, drive a car that suits you. A Jeep, a Subaru, a Mitsubishi, or (gulp) a Land Rover. Natalie, the kids, and I love our Subaru

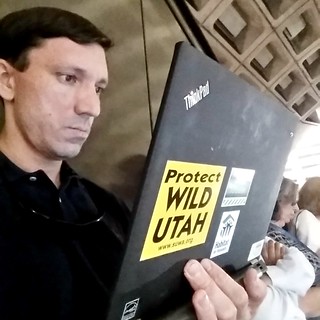

Working for Banff on the subway.

and it’s our getaway car for reaching quiet places where we can skip stones. Just don’t cover your new ride with stickers if you’re over 30. And if you’re not living in it, which I’m guessing you’re not. Save those stickers for your laptop.

If all else fails, move to the mountains. Get the support of your loved ones. Transfer the job or find a new job. If it doesn’t work, then you tried. I tried; the timing wasn’t right, and I’m more at peace for trying so damn hard.

Thanks again for stopping by. If you enjoyed this post, please consider following The Suburban Mountaineer on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.