Mt. Kennedy of the Yukon. (All rights reserved.)

I started to feel like I was missing something significant. Alpinist Magazine had a feature on Mt. Kennedy. Then my Google alerts showed a lot of “chatter” about Mt. Kennedy and suddenly Gripped Magazine had an article. Was Mount Kennedy the Mountain of the Year?

Well, not exactly, but there are two stories, and both are worth talking about.

In 1965 Jim Whittaker led Senator Robert Kennedy on the first ascent of an alpine objective in Yukon Territory formerly named East Hubbard, renamed by the Canadian government that same year after the late president, John F. Kennedy, Jr. I’ve often dismissed the ascent as notable but not significant. David Stevenson made it more interesting for me than just notable.

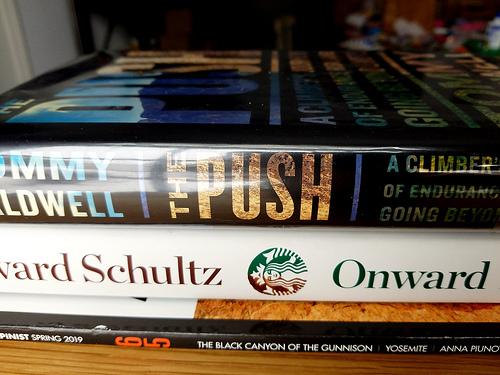

David Stevenson was a member of Mt. Kennedy’s second ascent in 1977. He also wrote the long-form feature — a mountain profile — in Alpinist 67. The mountain was remote, and it has all the elements of classic David Roberts and Bradford Washburn far north American alpine adventures, including long slogs, shuttling, and no contact with the greater world for months at a time and being at complete peace about it. I read that stuff with nostalgia. (Does that make me weak, or subconsciously critical of my modern hurried life?) Regardless, the feature was excellent and worth the purchase or the subscription.

The second story was a new feature-length documentary will be released this fall (fall 2019) about the sons of the original climbers, including a candidate for governor, a band manager, and young mountaineer, repeat of the climb 50 years later, Return to Mount Kennedy. Like most other climbing films (or any film or movie for that matter), I won’t rush to watch it, but I am curious about how the film delivers on its promise to tie in a theme of conservation.

Mt. Kennedy isn’t the mountain of the year. Who am I to declare that? But that does give me an idea for this blog; perhaps I have mountains or climbers of the month that I can focus on here on the blog and social media? Well, it’s just a thought.

Thanks again for stopping by. If you enjoyed this post, you might want to follow me on Twitter and Facebook.