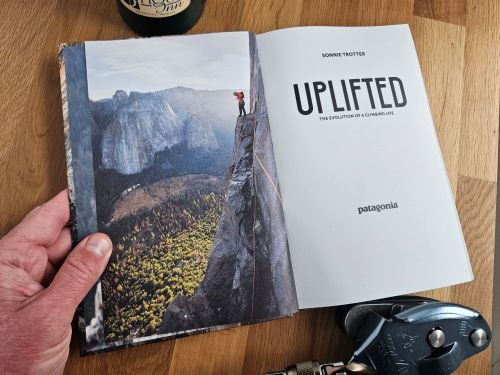

At first, I was puzzled. I was reading Sonnie Trotter’s book, Uplifted: The Evolution of a Climbing Life, from Patagonia Books, and wondering what he was doing here. Most climbing memoirs or autobiographies capture some grand incident that changed their life.

Think of Tommy Caldwell’s book, The Push; the ascent of the Dawn Wall was what people bought the book for, but it was the kidnapping in Kyrgyzstan that sent ripples through his life. A similar thing happened with Steve House’ book, Beyond the Mountain; we came for his climb on Nanga Parbat and we learned about his overseas exchange in Slovenia and indoctrination into their style of alpine climbing. What did I come to find in Uplifted?

I wanted Trotter’s story, but I couldn’t tell whether sure he knew, when I started out. Part of my irritation was that I was reading it via PDF; I could read the words, but with each page opening where the even pages were on the right and the odd numbers on the left, I was constantly sliding and zooming, and I couldn’t tell where I was in the scope and scale of the volume, by just checking how far the bookmark had advanced. Nearly three-fifths through, and it was abundantly clear that Trotter’s book was a different kind of book than Caldwell’s or House’s.

Trotter had, in essence, been writing the pieces that culminated into Uplifted for most of his climbing career. Some were his personal essays, some were published in magazines, and the book was in development prior to the pandemic. The result is Uplifted is Trotter’s collected works, shared chronologically (or at least that was his intention, according to interviews), largely with unpublished works, and we get to know Trotter even better than we did, and I started to understand what the book did well and did not.

Part of puzzling over this book was I was enjoying it, but it was different; I keep thinking of all that things that Uplifted is not. It isn’t about uncovering a new lens on Yosemite climbing. It isn’t a survival story. It wasn’t written in a cathartic fever. It isn’t a story about firsts, mostly. It isn’t about a turning point that shaped his career.

Well, on that last concept, maybe it all starts with discovering climbing on television on ESPN and then that a climbing gym opened near his home. It’s akin to an accomplished professional tennis player referencing how a city health program introduced them to the court and gave them their first racquet. The rest of incorporating their passion into life.

What do we learn about how Trotter lives? He loves life in a big way, he loves the people in his life, and he has a passion for climbing that is energizing to the reader. He has had heavy moments, but he has made a life balancing the climbing life with “real life,” or whatever that means. Trotter’s book recounts his climbing career and how it’s part of him and how he and climbing has matured together. If there is a biographical plot to this assemblage of stories, that’s it.

My sole complaint is that Trotter and his editors didn’t go all the way and carve all of these stories into a one steady narrative. It has the parts, and I enjoy a long-read. Perhaps that was everyone’s hesitation. It is Trotter’s collective works, rather than his literary opus.

The beautiful hard copy just arrived here at my house a few days ago. It helped to have the text on paper in its fine binding so I can enjoy the reading process flipping pages forward, and sometimes back to reread a sentence. The book also has beautiful photos and the paper is appropriately think; Uplifted deserves to be displayed on a coffee table, if not just your shelf. Perhaps it’s the short-read, versus the long-read nature, with the photos that make me feel it’s suitable for the table. (It’s a vertical rectangle shape is conducive to reading, but perhaps it should have been a square or horizontal rectangle for laying on a flat surface? Personally, I like the way it was done, but it tries to do more and it makes me overthink it. Does it make you consider it’s approach too?)

Could Uplifted be a classic one day? I think it has the potential to be timeless. It’s not about a milestone in climbing events, but it is a memoir or some sort, about climbing in our time and about a milestone climber. I am giving it a five out of five because I enjoyed it thoroughly and plan to reread portions if not all of it again.

Bottom line is that it’s just a good read. I know you’ll enjoy it.